Jill Cook

THE OBJECTS AND THEIR ORIGINS

Just over a century has elapsed since the discovery and acceptance of cave art at Altamira I. Since then many other such sites are known from Spain, France, Italy, Belgium and Britain (fig.1) II. Some are world famous and much admired as the oldest known European art but they were not the only art works of this period. Many small, portable sculptures, drawings, models and ornaments were made outside in the daylight areas of the cave entrances, in camps set up in the shelter of cliffs below roofs of overhanging rock or, in parts of Europe and Eurasia where such protection was not naturally available, on open ground campsites in and around well-constructed tents or cabins with skin walls. It is these images that are main subject of the exhibition.

Fig. 1. Map of sites mentioned in text

Made from or on bone, antler, ivory and stone, small works of sculpture, drawings and ornaments are numerous. Such portable or miniature art objects are often found amongst the remnants of everyday life such the remains of animals killed for food and materials and stone tools but some appear to have been placed apart or in special arrangements. Many are made with great skill by practised artists. The sketched, imagined, realistic or caricatured images displayed on them are those of the same animals depicted in the deep passages and chambers underground but their audience and significance may have been different. Like the painted caves, they reveal conscious human beings capable of imagining, thinking, reasoning and, above all, communicating in words, pictures, symbols and music. These are faculties of the mind which are supported by a well-developed brain. By identifying the use of imagination, abstraction, composition, perspective, dimension, the perception of space, scale and form within the painted caves and on the portable works, it is possible to see that the brain was functioning then as it does now. In this neurological sense, it may be said that all art is the product of the modern brain III and images from the last Ice Age are part of the long history of art. To understand something of its origins it is necessary to consider the engine which powered it.

ART BEGINS WITH THE BRAIN

Creativity is a faculty of the mind which is uniquely human and the battery which powers it is a complex brain with a well-developed prefrontal cortex. This area, at the front of the brain, powers all our ‘executive’ functions such as creativity, planning and decision making, as well as social behaviour IV . The complex modern brain is essential for the production of art. It evolved slowly over two million years but, whereas it is possible to trace the evolution of the human skeleton through time by research on preserved bones, skulls indicate relatively little about the complexity or capabilities of the brain. The appearance of representations of animals and people, as well as imaginary beings, patterns and symbols in Europe about 40,000 years ago indicates the arrival of the modern brain and the creative mind it supports. To understand where, as well as something of how, such modernity developed, and to discover the first signs of symbolic expression, it is necessary to turning the clock back and trace what is known about the evolution of our astonishing brains.

Charles Darwin wrote that it is easy to appreciate that the human skeleton relates to those of the great apes with which we share so much of our evolutionary history, but the difference in our mental skills might cause some people to doubt that conclusion V . Understanding what makes us conscious, thinking beings distinct from other animals, including chimpanzees our nearest genetic relatives, depends on neurology, the science of the brain VI. Neuroscience has developed dramatically in recent times thanks to the invention of various methods of scanning which provide images of how the brain is activated by different types of activity, as well as thorough case studies of the impediments suffered by patients with damage in particular areas of their brains . Even more complex research involves mapping brain cells and their connections. This has not yet progressed beyond the nematode worm but will in the future be as revolutionary in the understanding of our grey matter as the mapping of the human genome has been in describing our origins, relationships and causes of disease VII.

All animals have specialized nerve cells called neurons. Each minute cell might be imagined as like a tree with numerous branches and twigs. The points at which parts of each cell touch one another are called synapses. They provided pathways along which information can be transferred by chemical and electrical signals. This is what scientists now refer to as the ‘connectome’. The formation and deletion of neurons and synapses in the human connectome has changed through time along with our genetic make-up and variation in the signals being passed through the network as a result of external stimuli and experience. As a result of this evolution, the modern human brain enables us to communicate and utilize complex, even abstract, thoughts via the symbols of words and images. The proactive creativity promoted by this super highway of little grey cells allows us to transform the world through technology and culture.

In the simplest organisms the transfer of information along the synapses enables the central nervous system to produce reactions for food, sex and defence in response to external signals. In animals with brains, the connections are more complex, enabling not reactions, but some communication of information about food, readiness to mate and danger, by signals such as vocal calls and displays but only humans have evolved the capacity for proactive behaviour by externalizing their thoughts in language and by making things. This has not only enabled humans to use culture and technology to break down the barriers which environment imposes on all other animals, it has also given us the peculiarly human capability to recognize and speculate on times past and future VIII. This is the ‘eternal present’ of a fundamental instinct for art that gives us a thread of connection through time and a notion that part of our life continues after death as the discovery and reinterpretation of ancient works places them within our perceptions and times.

Fig. 2. Stone handaxes from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. (Height 13.6 and 23.8cms)

Within the archaeological record, it is stone tools known as handaxes that provide the oldest evidence of humans with a brain capable of externalizing thought (fig.2). Earlier choppers, chopping tools and flakes were a simpler technological response to obtaining sufficient food which in turn fed the calorie hungry brain in its development but handaxes seem to go beyond this X. Many are not only made for a job, they are made to look good. Their size, consistency of shape, symmetry and the selection of materials from which they are made, suggest that they were not purely functional objects but carried messages from, between and about their makers. They show the clear use of a mental template to produce three dimensional forms which bear little or no resemblance to the lump of rock from which they were made using another stone as a hammer. This requires some of the executive mental capabilities such as planning, decision taking and making which use the pre-frontal cortex perhaps stimulating its development. Modern experiments, in which the brains of participants who have just made a handaxe were scanned, show that the active area of the brain used for the activity overlaps with that used for speech suggesting that making things and talking developed together as out earliest ancestors had to find new ways of bonding and interacting XI.

Handaxes first appear in the archaeological record of East Africa around 1.6 million years. Their makers gradually spread out into South Asia, the Middle East. Eurasia and Europe around one million years ago and handaxes changed very little for about a million years. The mind that produced them was a limited, perhaps proto-mind, but may also have been developing in ways that leave no physical trace in the archaeological record. For example, sharing food or bonding through music could have involved thought processes capable of representing emotions through which the cognitive, executive abilities of the mind continued to exercise and develop the frontal area of the brain XII.

If handaxes indicate what could be described as the valve radio stage of what early human brains could receive and transmit with some intermissions and interference, then the modern brain is like the internet, a super highway capable of sending, storing, transforming and communicating huge quantities of diverse information. The intentional communication of ideas, the use of imagination and activities which may have psychological or emotional value all indicate the presence of a modern super brain capable of supporting the proactive, thinking, reasoning, creative mind. Evidence of this begins to appear in the archaeological record over 100,000 years ago in Africa.

THE APPEARANCE OF THE MIND

Discoveries of fossilized skeletal remains show that anatomically modern humans evolved in Africa between about two hundred and one hundred thousand years ago but such bones do not reveal whether the brains of these ancestors were as complex as our own. Evidence for the development of the brain has to be interpreted from the artefacts and remnant features of living arrangements found by archaeologists. In Southern Africa a number of recently excavated sites now indicate that between about 100,000 and 60,000 years ago new features appear in the patterns of behaviour preserved by the archaeological record. These novel characteristics do not simply relate to variations in hunting or gathering practices caused by environmental changes. Instead, they suggest that people were starting to invent activities that assisted the social, emotional or psychological aspects of their survival in a process which might be called unnatural or culturally assisted selection. These characteristics are often associated with modernity.

The appearance of carvings, engravings and the use of pigments as paint and crayon have no practical explanation. They suggest the invention of self-conscious activities that help people come to terms with themselves, with nature and, perhaps, through belief systems, with the forces that they perceive as governing the natural world. They are evidence that anatomically modern humans not only evolved in Africa but developed behaviours that encouraged the development of the modern brain.

A similar process was occurring simultaneously in Europe where Neanderthals who shared the same ancestors as in the modern humans who evolved in Africa, not only developed tool making technologies that required planning and decision making XIII but also occasionally buried their dead and made use of personal ornaments such perforated animal teeth and shells XV , as well as bird feathers . However, evidence of symbolic thought and its communication is not frequent, consistent or widespread until the arrival of fully modern humans in Europe and perhaps suggests that the shape of the modern skull allowed greater development in the frontal area of brain crucial to communication and creative skills XVII.

THE ARRIVAL OF THE MODERN MIND IN EUROPE

Modern humans began to migrate into Europe around 50,000 years ago. The oldest known examples of painting, drawing, sculpture, music and personal decoration are known from Germany, Italy and France around 40,000 years ago XVIII . Unlike the known African examples, these works are figurative. They represent animals, people and imaginary beings. It is the latter which are most clearly indicative of the complex brain supportive of a modern mind. A simple mental image of a person or animal does not necessarily require a brain like our own but it is essential to conceive a part human – part animal representation.

From the start, the universal laws of art devised by neuroscientist Professor Vilayanur Ramachandran are in use XIX. Realism was not always the goal. The artists were simplifying, exaggerating and distorting to engage the mind of the viewer. Abstraction, caricature, metaphor, grouping, contrast, balance and isolation are all used to intrigue and stimulate the viewer’s attention to a virtual reality with meaningful implications for the real lifestyle. They achieve this so well that modern viewers are still exercised by them. Although they stand far outside our own cultural norms, our visual brains cannot help but connect, puzzle and interpret for our own time. Although academic archaeological strictures may forbid this, our brains can see that messages were intended and cannot resist the signals which bid us to try to read this lost language.

What prompted the appearance and proliferation of art towards the end of the last Ice Age in Europe is uncertain. Migration into new territories and the stresses of adapting to new habitats may have activated psychological stimuli to organize, regulate, empower or overpower certain aspects of life through image and story. This is possible but it was not the pioneers who made images and ornaments, it was their descendants who after several generations had successfully acclimatized.

A more significant stimulus for art may in fact come from the need for people to bond and socialise effectively in order to survive in environments in which they were vastly outnumbered by other animals. Surviving by having enough food and being able to keep warm is only part of the human story. To transcend the barriers imposed by environment and maintain genetically viable populations, humans had to form good social relationships. This is only partially achieved by language as what is expressed in speech is often transitory and open distortion. Being able to fix ideas in images provides a better basis for sharing concepts that promote cohesion, collaboration and a more stable adjustment to environmental circumstances by sustaining or, perhaps, regulating relations between individuals and groups. New means of negotiating, mitigating and holding secular and possibly spiritual power needed to be worked out to sustain agreement and cooperation. All of these pathways required thoughtful responses, demanding more complex communication of ideas, emotions, stories and metaphors. Figurative and decorative art, which was clearly valued through the investment of time, specialist skills and resources it received, was an important agent in this process. It is in art that we recognise the essential abilities needed in creating relationships with each other, nature and the cosmos that are crucial to the viability and sustainability of expanding populations.

LANDSCAPE, ANIMALS AND LIFESTYLE

22,000-12,000 YEARS AGO

In the popular imagination, the Ice Age is associated with persistent snow and ice cover as the name implies. Whilst this was true of some places at some times, it was not always cold and glaciated (fig.3). Although conditions were generally colder than at present right through the period from 45,000 to 12,000 years ago, the climate was unstable and fluctuated considerably over timespans of a few thousand years.

Around 22,000 years ago temperatures again began to dip into a period that was extremely cold and dry throughout Europe during what is known as the Late Glacial Maximum. Ice sheets expanded over northern Europe and glaciers filled the valleys of the Alps and Pyrenees. With so much water locked up as ice, sea levels were lowered and the geography of the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts was quite different. Ecosystems were also distinctive supporting communities of plants no longer found to together but surviving in tundra, taiga and alpine environments. Although known from pollen records, Plants are not represented in art at this time perhaps because not being animated they were not conceived as part of the living world.

By contrast animals are the most frequent subjects of Ice age artists. They include species now found far to the north around the Arctic Circle such as musk oxen, reindeer and wolverines existed then alongside bison and horses in southern France and central Spain, as well as mammoths that became extinct about 13,000 years ago in these areas. Milder conditions on the Cantabrian coast and in sheltered valleys of southwest France supported more red deer and ibex were abundant in the Pyrenees. All of these animals are depicted in the art and human food remains of this period although the frequency with which animals are depicted does not always correspond with their significance in the human diet. For example, in Cantabria the ibex depicted on items of portable art and ornaments and the bison represented on cave walls are infrequent in food remains in which red deer remains predominate XX.

Human lifestyles had to adapt to extremely harsh conditions. Although there was some improvement after about 20,000 years ago, large areas of northern Europe, including Britain, remained unsuitable for habitation. Warmer, wetter conditions did not reappear until roughly 15,000 years ago but then lasted only a short time before another short, cold period known as the Last Glacial Maximum, which preceded more constant warming.

Bands of people living by hunting and gathering set up camps under rock overhangs or in the daylight areas of caves but where nature did not provide shelter, tents or houses with skin walls were constructed in small, village-like groups. Hearths were the focal point of every community and throughout the period often appear as well-defined features with stone surrounds. Fire was vital for warmth, light and protection from predators, as well as cooking and socializing. Not allowing the fire to go out would have been an important task. The hearth was the place where people shared food, information, told stories, laughed, sang, danced, negotiated and quarrelled. It was perhaps the place where they found their creative inspiration.

Fig. 5. Flint engraving tools found at La Madeleine, Dordogne, France. Known as burins like their modern metal counterparts, the flints are shown with their working tips at the top.

Tools and weapons were made from stone, bone, antler and ivory. Their types vary through time and geographically and some are particularly diagnostic of archaeologically defined periods. By about 15,000 years these kits had developed to include many items designed and mode for particular jobs. There were various types of spear and dart tip made to kill with maximum effectiveness small, medium or large game, birds or fish. Hooks and gouges were made for line fishing. All these things had to be made and the materials needed for them had to be collected. The living was not easy but it was sufficiently successful to support practised artists who were allowed to spend many hours producing sculptures, drawings and paintings. The evidence for this comes from the careful observation of the characteristics of cave painting, engraved drawings and sculptures some which may be described as masterpieces.

Fig. 3. Map showing the extent of ice sheets, glaciers and the geography of Europe during the last Ice Age.

In art historical terms the definition of a masterpiece is a work that shows technical virtuosity, as well as ground breaking skill and originality used in the production of works that are charged with power often giving a sense of the supernatural XXI . Many cave paintings and portable works such as the swimming reindeer from Montastruc, Bruniquel, France (cat.) and the ibex head from Tito Bustillo (cat.) reveal these qualities when examined closely. In the case of the former, the tip of a mammoth tusk has been brilliantly transformed by conceiving a representation that would utilise the tapering, conical form of the material to best advantage and with some economy in a realistic but highly original composition of a larger male following a female. The heads of the animals are raised and the legs outstretched in a manner that suggests they are swimming as they do when on migration. This composition allows the reindeer to be shown as large as possible whilst removing the least amount of ivory.

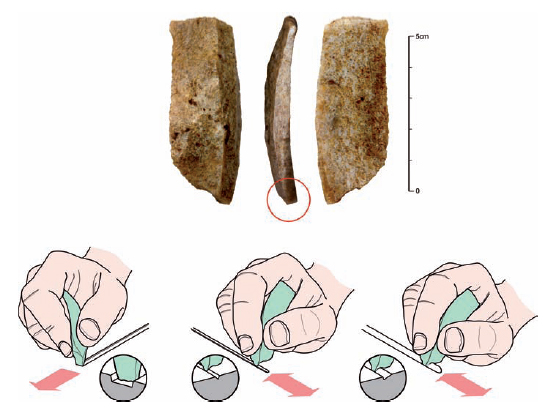

Fig. 4. A burin in use. Held like a pencil, the character of the line being engraved can be varied by using the full width or a corner angle of the working edge.

Detaching the tip of the tusk took time and experience. It was probably done by making a deep groove around the circumference and then chopping into it with a stone chopper. The outline shapes of the figures were then shaped using stone blades and engraving tools with narrow working ends called burins like their modern metal counterparts that could be held and used like pencils to sculpt and engrave the details (fig.4). Ivory is hard and cannot be softened with water but regular applications of water certainly help to maintain the edge on the tool. Sculpting the animals took many hours of hard, patient work that was perhaps meditative for the artist who had the ability to represent the animals scaled down in perfect proportions. The confidence of a well-practised hand can be seen in the quality of the relief and engraving work. Examination of the piece using digital imaging microscopy and Raman spectroscopy has revealed the sequence of work and the identity of colouring and/or polishing agent XXII . The engraving was done after the basic shapes had been polished. This was possibly done using the red ochre identified on the surface as a buffing agent applied with water and a soft piece of leather. The engraving was then carefully applied and shows no indications of correction in a variety of shading techniques that emphasise the body contours, highlight the facial features and differentiate the colour and texture of the coats.

The details of sequences such as this indicate the virtuosity, artistry and originality of an artist whose work had social value and support. The investment of effort and skill in painting and engraving in caves similarly suggests that this work that did nothing to feed or clothe anyone was nonetheless regarded as important and life enhancing.

The equipment used by artists was not particularly special or elaborate but required time and organization to assemble. The stone tools used for engraving drawings on portable pieces, as well as cave walls were no different from those use every day for the manufacture of spear tips and needles (fig. 5). Powdered ochre which provided a variety of red, yellow and brown colours was a pigment which might be applied wet or dry but it also had practical applications and used extensively in the process of softening skins. Ochre is an iron oxide which occurs naturally as in clay and had to be collected from natural exposures. It is soft enough to quarry out in small pebbles with a bone or antler tool. Some pebbles were shaped and used as crayons, others show scraped surfaces which would have been a measured way of providing an amount for a particular job, such as highlighting the lines of an engraving but larger quantities of powder for the polychrome and filled paintings in the caves were produced by grinding up the nodules on stone slabs. Manganese dioxide which provided black had to be collected and prepared in the same way and charcoal was produced in the hearths. Most of the paint was applied with the fingers, ball or edge of the hand or sprayed from the mouth. Leather pads filled with moss may also have been used to apply bigger areas of colour in the light of burning wooden torches or dished stone lamps fuelled with animal fat which provide the equivalent of candle light. In some sites wooden ladders or platforms lashed together with rawhide would have been necessary to work on surfaces high above the head. The equipment was amazingly simple but the results remarkable.

In their content and their craft the images made in torchlight on the walls of caves and those made in daylight on small supports share many characteristics although there seems to have been a different relationship between audience and image in these locations. Whereas the passages and caverns of the painted caves produce few finds of human debris, the portable art is surrounded by it. This has led to the caves being regarded as sanctuaries, cathedral-like spaces where artists and audience took part in social and/or spiritual rites. These rites may have been communal in large spaces whereas engravings tucked away in narrow or low niches suggest individual devotions. Footprints in some caves indicate that the participants were adults sometimes with children but whether they were all men, all women or included both sexes is unknown and may have varied.

By contrast the portable art was made and seen in the daylight. It could have been shared or personal and sometimes the act of drawing may have been as important as the end product. The naturalism of some works is evocative of how close these hunter-artists were to nature, while at the same time separated from it by their intelligence. This intelligence is expressed in their ability to symbolize their world in images through which they might reshape or even transcend it through storytelling or perhaps in beliefs. In this way they were crucial to the survival and development of early modern human societies. Although their meanings and messages elude us, we can nonetheless appreciate the quality and originality of these works and see that the modern brain then as now used art not to reproduce the visible but to make things visible XXIII.

Annotations

I M. A. GARCÍA GUINEA, Altamira y otras cuevas de Cantabria, Madrid, 2004.

II A. J. LAWSON, Painted Caves, Palaeolithic Rock Art in Western Europe, Oxford, 2012, págs. 15-105.

III V. RAMACHANDARAN, The Emerging Mind, Londres, 2003, págs. 46-69.

IV E. GOLDBERG, The New Executive Brain: frontal lobes in a complex world, Oxford 2009.

V C. DARWIN, The Descent of Man, Nueva York, 1871, pág.83.

VI V. RAMACHANDARAN, op cit. nota ii, Londres, 2003, págs.1-26.

VII J. F. HOFFECKER, Landscape of the Mind. Human evolution and the archaeology of thought, Nueva York, 2011.

IX S. GIEDION, The Eternal Present. The beginnings of art, Nueva York, 1962, págs. 2-3.

X N. MACGREGOR,

XI D. STOUT et al., «Neural correlates of Early Stone Age toolmaking: technology, language and cognition in human evolution», Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B, 2008, vol. 363 (1499),

págs.1949-1949.

XII C. GAMBLE et al., «The social brain and the shape of the Palaeolithic», Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2011, vol. 21 (1), págs. 115-136.

XIII J. ZILHÃO, «The emergence of language, art and symbolic thinking. A Neanderthal test of competing hypotheses», en C. S. Henshilwood & F. d’Errico (eds.), Homo symbolicus. The dawn of language, imagination and spirituality, Ámsterdam, 2011, págs. 118-119.

XIV P.PETTITT, «The living as symbols, the dead as symbols», en C. S. Henshilwood & F. d’Errico (eds.), Homo symbolicus. The dawn of language, imagination and spirituality, Ámsterdam, 2011, págs. 141-161.

XV J. ZILHÃO, op cit. nota xvi, en C. S. Henshilwood & F. d’Errico (eds.), Homo symbolicus. The dawn of language, imagination and spirituality, Ámsterdam, 2011, págs. 120-123.

XVI C. FINLAYSON et al.,«Birds of a feather: Neanderthal exploitation of raptors and corvids», PLoS ONE, 2012, vol. 7 (9): e45927.

XVII E. PEARCE, C. STRINGER, R. I. M. DUNBAR, New insights into the differences in brain organisation between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans.

XVIII J. COOK, Ice Age art: arrival of the modern mind, Londres, 2013.

XIX V. RAMACHANDRAN, op cit., nota ii, Londres, 2003, pág. 50.

XX BARANDIARÁN, I., Arte mueble del Paleolítico Cantábrico: una visión de síntesis en 1994. Complutum, 1994, vol. 5, págs. 45-79.

XXI K. CLARK, What is a masterpiece? Londres, 1979.

XXII J. COOK, The Swimming Reindeer, Londres, 2010.

XXIII Citado de Creative Credo, Paul Klee, en H. B. Chipp (ed.) Theories of Modern Art, Berkeley 1968, pág. 182.