MARÍA BLANCHARD

Cubist

Introduction

The exhibition entitled María Blanchard. Cubist is an important milestone in the Fundación Botín’s proven track record of organising exhibitions. This is mainly thanks to the opportunity resulting from our joining forces with the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía to bring to fruition a project that the Foundation had in the pipeline for a long time.

This exhibition, which will be subsequently put on in Madrid, seeks to position María Blanchard, a universal artist born in Santander, in her deserved place as a key figure in the artistic renovation at the start of the 20th century.

Presentation

The exhibition of María Blanchard and the accompanying catalogue represent an important landmark in the Botín Foundation’s extensive work organizing exhibitions. To a large extent this is thanks to the opportunity which arose of uniting our efforts with the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía to finally make possible a project the Foundation had been preparing for a long time.

The objective of both the exhibition and this publication is to help put María Blanchard, a universal artist born in Santander, in the place she deserves as a key player in the artistic resurgence at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The early years of last century, when María Blanchard lived and produced her art, were years of great industrial, technological and social transformations. In this climate, creative thinkers and artists played a crucial role. Their contributions helped to revolutionize art as they sought new formulas to represent their world and adapt it to modernity. In this way they were a faithful reflection of the spirit of their times.

Now in the midst of the twenty-first century, the Botín Foundation is convinced that today’s art and culture have a crucial role to play as a driving force for social, cultural and economic development. Art and the arts have a unique power, unlike anything else, to awaken individuals’ creative talents and to set in motion their emotions to generate the type of attitude required to invent new ways of doing things.

For this reason the Foundation will continue to support the arts in the future, investing resources and energy to encourage and promote its programme of research, training and dissemination of knowledge which it has been developing now for 25 years.

I would like to thank the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, the private and public owners who have kindly loaned works from their collections, the exhibition’s curator, María José Salazar, and the entire staff who have worked to instate María Blanchard and her transformative art to their rightful place in history.

Emilio Botín

President of the Botín Foundation

María Blanchard grew up among the branches of Cubism, a movement that had brought about a modern reorganization of our way of seeing the world. In effect, the movement formed the Gordian knot of a comprehensive reinterpretation of our surroundings which had been initiated years before being conveyed in canonical terms by Picasso, Braque and Juan Gris. However, its totalizing intent, its revolutionary power for alteration of the principles on which the theory and practice of painting had been based since the Renaissance, soon ran into a situation that overwhelmed any initial proposal: the expansion of its message and the wide variety of approaches to Cubism employed by new artists overflowed what many people had regarded merely as an artistic style and converted it into a almost indefinably plural and polyhedral category. These outlets cannot be understood without the advent of the Great War and the impact it had on the universal collective consciousness, nor without the responses the conflict provoked, which were often part and parcel of the restrictive caption that defines a reactive act: the “return to order”.

The plurality of the less powerful aftershocks emerging from the vast land shift caused by Cubism is perhaps the thing that provides us –from a new perspective of the History of Art– with an image of the twentieth century as a complex map where the local, the reactive, the apparently derivative and the late-arriving assume new roles; being one facet of the polyhedral compound of modernity. In this context, María Blanchard’s oeuvre is a case study interlacing diverse elements that have gradually come to light during the research process prior to this exhibition – namely questions related to her gender, social and physical condition and religiousness. Blanchard’s output as a painter emerges from this as displaying strategies of adaptation and survival against the onslaught of History, but also against the social limits imposed on the female condition which the artist found it difficult to comply with. In this sense, the light shed by new studies about women joins forces with the instruments at our disposition to reinterpret the artistic movements of the period from a new perspective.

One often-quoted anecdote provides us with a first pointer: Léonce Rosenberg, who was María Blanchard’s art dealer during the middle part of her career, refused to accept the artist’s work during the sales crisis in the 1920’s and the falling market value of a certain style of Cubism. However, seen in retrospect, Blanchard’s work at a time underwent a subtle reaction to this cul-de-sac affecting the Cubist language when its survival depended not so much on forging a grammar as on the development of dialects. It is due to this elaboration of languages –where the local, the familiar and the intimate have more weight than the articulated or the normative– that questions previously regarded as derivative or mannerist take on new worth. The centre cannot be sustained without the influence of the periphery. The previously mentioned art dealer’s act of rejection leads us, however, to confront a fact: María Blanchard was, in many senses, an outsider, a human being who found it hard to fit in easily with the models available to her as an artist and as a woman in a specific social context. Accordingly, to get carried away exclusively by biographical-style interpretations of her work (in the disproportionate manner that has been applied to Picasso) would be as big a mistake as completely ignoring the vital framework which transpires in a large part of her output, namely that María Blanchard was a woman marked by a physical deformity living in an age when the return to order imposed, in the French scene, classical concepts like grace and charm, applied as an stylistic canon and therefore having a direct effect on the construction of gender.

The Freudian concept of the uncanny –that which is at the same time mundane and strange, familiar and disturbing, like mannequins, dolls or wax figures– seems increasingly to crop up in her painting, and by confronting this the artist moves away from a superficial Cubism, which heralds its own demise, to tangentially touch upon a number of additional aspects that are able to breath life into the movement and pluralize it.

One needs to point out, along these lines, that María Blanchard found her place in the world only after she was able to force her posture from the woman-object to the woman-individual, thus distancing herself from other contemporary artists who still alternated between the artist and the model. In this fashion, from the perspective of her special condition she broke the idea of the painting as a window and also rejected the canvas as a mirror. It does not seem farfetched to hazard a nascent pre-feminist conviction in this decision; just as it is invariably fascinating that, of all of the stylistic options available to her Blanchard should choose the one that was most perilous, even in the Paris of the day.

Her attempt to view the world differently, something Marcel Proust had yearned for too, seems to be underpinned by a desire for the view to be returned one day, not as a reflection, but as a response fully aware of her physical appearance, which at the time was branded as monstrous. It is in the period from the end of the First World War until 1932, the year of her death, when she, unlike many of her contemporaries, took Cubism to the border of abstract painting. In doing so she pursued a series of recurring themes, which despite having sentenced her historically to the sidelines of the art establishment due to their difficult synthesis with the unambiguous discourse of modernity, appear today as a powerful reaction against two types of limitation: on the one hand, the hermetic iconographical repertoire Cubism provided her with; on the other, the impositions related to gender. Consequently, she inhabits a terrain between rediscovered religiosity, which has been barely taken into account up until now, and insistence upon classical themes associated with a feminine world view, perhaps in ultimate pursuit of an alternative femininity. Blanchard moves away from Cubism as a way of questioning bourgeois views towards inner, personal subjects, mother and child scenes, and family groups. Her dialect turns into a koine, the common language of her own universe.

Some questions arise when we take all these aspects into account. What new channels can her painting open up if we revaluate her Post-Cubist style and give it a similar treatment to that of other artists who are fully accepted today – such as, for example, Medardo Rosso, who brought an entire world into question using a limited iconography originating from the outside? What new channels can be opened up by regarding her work as representative of the interplay of advances and retreats that define the twentieth century?

The exhibitions organized by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and the Botín Foundation provide keys and offer suggestions: firstly, at the venue in Santander, the exhibition will focus on the Cubist period, thus raising the first challenge against any univocal view of the movement and serving to gauge the artist’s individual contribution; secondly, at the Reina Sofía Museum, an overview of the artist’s entire oeuvre will tackle her personality in various contexts –in Spain’s Regeneracionismo and interwar Paris– a panoramic view in which her wide range of voices may be heard.

In the Elegy written by Federico García Lorca on occasion of María Blanchard’s death, he referred to the artist as “a shadow”, as someone who was “frightened in a corner”; this shroud of darkness, which neutralized the full potential of her work over the years by overlooking the questions mentioned earlier, has finally been lifted. The two exhibitions, which we introduce in this publication, will jointly shed new light on Blanchard on the 80th anniversary of her death, making no demands on her to abandon her introspective, only seemingly dark, realm wherein lies an entire world.

Manuel J. Borja-Villel

Director of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Iñigo Sáenz de Miera

Director General of the Botín Foundation

María Blanchard

The Great Unknown

- María Jose Salazar

Exhibition Curator

María Blanchard has been and continues to be the great unknown within the group of artists responsible for consolidating artistic renewal in the early 20th century. Despite the time that has passed, certain circumstances unrelated to her artistic development have led to large gaps and enormous contradictions in her life story and her work has remained in the background in comparison with that of her avant-garde peers and friends. However, Blanchard was equal and in some cases superior to the latter, above all in her particular way of understanding and perceiving Cubism.

Her various biographies have repeatedly focused on her physical appearance, giving the impression that this was the trait that definitively influenced her life and work, thereby fictionalizing her life and forgetting her struggle and artistic relevance. Although it is true that her appearance was a determining factor in her life, it is no less true that her strong character and tough existence earned her the respect of her colleagues, who came to accept her as an equal in an environment culturally dominated by men.

Many of her artistic contributions were forgotten due to the fact that when she died, and although she was working with important galleries in France and Belgium at the time, all her works were withdrawn by her family. This made it difficult for her work to be studied or disseminated and led to a long period of obscurity.

In Spain it also took a long time for her work to become known and even longer for her to be recognised as a great artist. This becomes clear if we consider that after the exhibition organised by Ramón Gómez de la Serna in 1915, Los pintores íntegros (Upright artists), her work would not be exhibited again until the Primer Salón de los Once (First Hall for the Eleven) which was held in the Madrid Galería Biosca in 1943. Only 33 years later, in 1976, would her work be exhibited again in that same gallery. The following year it was shown in Galería Sur in Santander and three years later in Sala Gavar in Madrid.

Similarly, there have been very few retrospective exhibitions about the artist. There have been three which are of particular interest due to their scientific approach. The first was held in the Paris Galerie de L’Institut in 1955 and focused on her cubist phase. The second retrospective took place in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Limoges in 1965 and was curated by Marie-Madeleine de Gabrielli. The third such exhibition was curated by myself and organized by the Spanish Ministry of Culture, in the Museo Español de Arte Contemporáneo, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of her birth with the presentation of her complete works for the first time in Spain.

There are many reasons for proposing this exhibition and they are all related to her cubist work (1913-1919), with a limited overview of her previous work (1907-1913), which influenced her subsequent work to a certain degree, and a third group of works which represent a return to Figurative Art during the final years of her life (1919-1932).

Her early works are lacking in specific artistic personality and, as in most cases, are susceptible to the influence of her various teachers. We can observe the presence of Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor, Emilio Sala, Manuel Benedito, Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa and Kees Van Dongen. However, it is important to note that her work during these first few years is far superior to that of many of the painters who were working in Spain at the time.

During this initial phase she focused her iconography on portraits, through which we can trace her development. She goes from subdued colours and solid lines, close to the subject, to a greater wealth of colours, somewhat expressionist, and a richer, denser subject matter, using palette knife and a looser style to gradually free herself from traditional atavisms.

Following this phase, during which she effortlessly assimilated the work of other great artists, she took her first highly characteristic steps in cubism, her least known work which has been overshadowed by the preference of critics and historians for her figurative compositions. However, if any woman can be considered to have been a great cubist painter, then it is María Blanchard. She passionately immersed herself in this movement which she had been familiar with since the First World War, as we know from the descriptions, reviews and texts about her work that we have received.

There is no doubt, in my opinion, that the cubist work of María Blanchard is superior to that of her well-known peers, such us Albert Gleizes, Auguste Herbin, Louis Marcoussis, Jean Metzinger and Fernand Léger. If we also consider the handful of women who sporadically produced cubist works, such as Sonia Terk Delaunay and Alice Halicka de Marcoussis, with very occasional pieces, or Marie Laurencin, the companion of Apollinaire at the time, we can appreciate the importance of María Blanchard within the cubist movement.

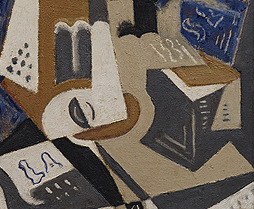

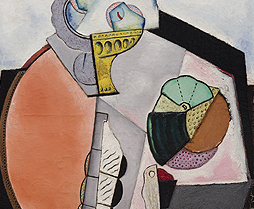

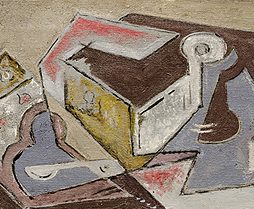

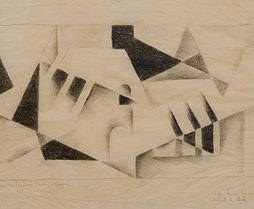

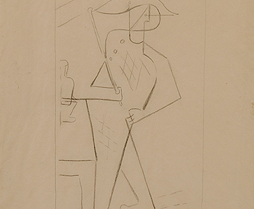

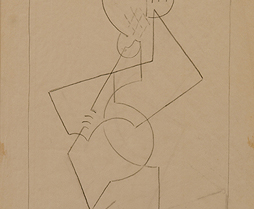

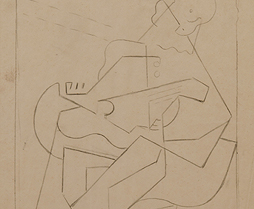

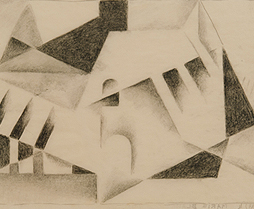

The work of Blanchard shows a clear progression. Her initial Cubism produces simple works with easily identifiable figurative elements which she represents by means of superimposed geometric shapes, in line with the work of Diego Rivera. She later evolves towards a more synthetic Cubism, hand in hand, no doubt, with Juan Gris, with whom she shares not only friendship but also aesthetic principles.

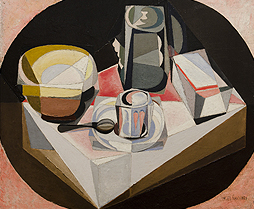

In these compositions the subject matter is limited to essential elements, expressed through planes which are viewed from different perspectives. These works are closely related to the musical compositions and still lifes of Picasso, Braque and Gris, in which the elements in question are represented objectively, sometimes using collage as a substantial component. However, María Blanchard shows greater freedom in her interpretation of the subject matter than the aforementioned artists. Her poetics in the use of colour gives her a clearly defined personality which somehow frames her work within the artistic parameters of Orphism, the name given by Guillaume Apollinaire in 1913 to a colouristic and rather abstract tendency within Cubism.

We are therefore looking at a highly personal form of Cubism which stands out for its formal precision, austerity and command of colour.

With these works she not only achieved success but also the recognition of art dealers, critics and artists. She did not found a movement but she did contribute to the development of Cubism, with the same standing and importance as other artists of her generation.

In practicing Cubism, María found a form of expression which allowed her to show that, at least in terms of expressiveness, she was on a par with the best avant-garde painters. This was a crucial moment in her life and work. She not only produced some of her best pieces but it was also a time for sharing experiences with her friends, some of the closest being Diego Rivera, Jacques Lipchitz, Juan Gris and André Lhote.

It is highly significant to note that artists of such stature had no qualms about accepting her in their group. Indeed, in the case of Rivera and Gris, she shared studios and spent long periods travelling around Europe with them, as well as attending the usual artistic gatherings in Paris. We must remember, once again, that she was a “female artist” in a creative world dominated by men.

Her work from this period attracted the attention of the most important art dealer at the time, Léonce Rosenberg, who gave her a contract with his gallery, L’Effort Moderne, in 1916. Three years later he organized her first individual exhibition of cubist works.

As her work became known, she received universal recognition. In 1916, she was selected by André Salmon to participate in the exhibition L’Art Moderne en France (Modern Art in France) which was presented at the Salon d’Antin in Paris. In 1920, she was chosen by Sélection magazine for the exhibition Cubisme et Neocubisme (Cubism and Neo-cubism) which was presented in Brussels, together with Picasso, Braque, Severini, Lipchitz, Metzinger and Rivera. The following year she formed part of the legendary show Exposició d’Art francés d’Avantguarda (Exhibition of French Avant-Garde Art) in the Sala Dalmau in Barcelona.

Her works achieved such quality that various publications confused them with those of Juan Gris and even displayed them under his name. In the forties, Kahnweiler affirmed that unscrupulous individuals had eliminated the signature of María Blanchard from certain paintings in order to add the name of Gris, due to his greater market value. Even Diego Rivera highlights the importance of her work: “Her time in cubism produced the movement’s best works, apart from those of our master, Picasso”. In the view of Jacques Lipchitz, María Blanchard brought expressiveness and, above all, feeling to Cubism.

Historians such as Waldemar George and Maurice Raynal highlight her great sensitivity and strong Hispanic character. They observe the latter in green, black and brown tones and, above all, in her favourite subject matter, still lifes, which are seen to be a continuation of traditional Spanish painting, following on from the work of Sánchez Cotán and Zurbarán.

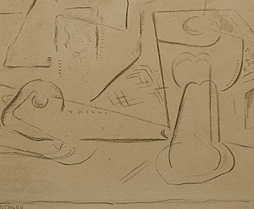

At the start of the 1920’s, as with so many artists at the time, her art evolved towards new forms which were indebted to her time in Cubism. Her foray into the so-called Retour à l’ordre movement was nothing other than a personal solution to her need for artistic development. The representation of objects moved towards a figurative style in which the geometric structure of cubism still persisted, whilst the volumetric composition and luminous arrangement brought them closer to the works of Cézanne.

She entered this new phase with her own form of expression, using the human figure as an heir to her inner experiences, thereby giving her work a characteristic personality. This is a very interesting period, with a turning point in 1927 which led to a more sensitive, melancholic and poetic iconography in which a profound sense of reality underlies the technique, colour and drawing.

Distinguished French and Belgium dealers of the time, such as Paul Rosenberg, Max Berger, Doctor Girardin, Frank Flausch, Jean Delgouffre and Jean Grimar sought out her work and signed important contracts with her.

There is no doubt that the life experience of an artist has an impact on their work but the clear influence of María Blanchard’s life on her work is a differentiating element which sets her apart. María brought the dramatic sense of her own existence to her work, giving a transcendental aspect to her figures. However, it was the very course of her life which paradoxically condemned her to oblivion. Perhaps its most dramatic elements, her illness, physical appearance and solitude, curtailed her recognition as an artist.

María Blanchard lived in complicated times, both for artists and women, which forced her to make harsh sacrifices, both in social and material terms, in order to devote herself entirely to painting. From a conceptual point of view, the transfer of experiences, pain and suffering to the figures portrayed on the canvas allows us to identify a certain parallelism between her work and that of the Mexican artist Frida Khalo.

Despite the fact that countless authors and critics have written about the artist (José Bergamín, Federico García Lorca, Gerardo Diego, Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Pierre Cabanne, Jean Cassou, Paul Claudel, Pierre Courthion, Maurice Raynal and Waldemar George, amongst others) her biography continues to be dotted with inaccuracies and our knowledge of her work remains insufficient.

This exhibition aims to pay tribute to the valuable contribution of a woman who devoted her entire life to art during the early years of the 20th century and was acknowledged by her friends, great artists, as one of the great. For Gris, the artist “has talent”, whilst according to Lipchitz, María Blanchard “was a sincere artist and her paintings contain a painful sentiment of unusual violence”. At the same time, for Diego Rivera, her work “was pure expression”.

Information

EXHIBITION MARÍA BLANCHARD. CUBIST

Fundación Botín Exhibition room

Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, 3. Santander

23 de June to 16 September 2012

Open daily: 10.30am a 9pm

ACTIVITIES AROUND THE EXHIBITION

Germaine Dulac. Views of integral cinema

Curator: Berta Sichel

Auditorium. Pedrueca, 1. 8 pm.

The screenings connect Germaine Dulac (1882-1942) and María

Blanchard (1881-1932), both early 20th century avant-garde artists.

19 JULY

PRESENTATION BERTA SICHEL

Disque 957, 1928

La coquille et le clergyman, 1927

Théme et variations, 1928

21 JULY

La souriante madame Beudet, 1922

Étude cinématographique sur une arabesque, 1929

L’invitation au voyage, 1927

31 JULY

Disque 957, 1928

La coquille et le clergyman, 1927

Théme et variations, 1928

2 AUGUST

La souriante madame Beudet, 1922

Étude cinématographique sur une arabesque, 1929

L’invitation au voyage, 1927

Discover Cubism with María Blanchard

Learning activity in the form of a tour-workshop

aimed at children from 6 to 11 years.

Exhibition room. Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, 3. 12pm to 1.30pm

Thursday, 19 and 26 July

Thursday, 2, 9 and 23 August

Thursday, 6 September

Lectures

Sala de Exposiciones. Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, 3. 8pm.

Thursday 19 July - Mª José Salazar, exhibition curator

Thursday 9 August - Salvador Carretero, director MAS

Guided tours.

By appointment. Telf. +34 942226072

Credits

Arts Advisory Commission

Fundación Botín

Vicente Todolí. President

Paloma Botín

Udo Kittelman

Manuela Mena

Mª José Salazar

Curator

Mª José Salazar

Head of

Exhibitions MNCARS

Teresa Velázquez

Coordinator MNCARS

Gemma Bayón

Coordinator

Fundación Botín

Begoña Guerrica-Echevarría

Amaia Barredo

Management

Natalia Guaza

Ana Torres

Registry

Clara Berástegui

Iliana Naranjo

Sara Rivera

Head of Conservation

Rosa Rubio

Conservation

Beatriz Alonso

Margarita Brañas

Cristina López

Exhibition Design Fundación Botín

Fundación Botín

TresDG/ Fernando Riancho

Insurance Fundación Botín

AXA art España

© Fundación Botín, MNCARS and authors